Lessons learned when building Serverless web applications - Part 2

With Serverless we get rapid provisioning, automation and consumption based billing. This enables new development and release processes that are just not possible with traditional applications and infrastructure. Add to this a DevOps culture and the dream to build, test, and release software faster and more reliably becomes true. This part of the Serverless lessons learned series focusses on Continuous Delivery.

First, let’s take a look at how this new development process differs from the traditional model. Then I’m going to describe our setup and what worked well for us.

Traditional development usually happens in a local environment, that is disconnected and often very different than the actual production environment. Depending on the size and complexity of the application, this could mean a long and tedious onboarding process for new developers. Containers are often used to simplify this, but even their setup and maintenance can become complex and may not resemble services used in production. Also this means infrastructure changes that developers perform in their local setup are not reflected on other environments. This leads to costly errors that are discovered very late in the process. You also typically have a limited number of dev and staging environments. I’ve actually seen people fight, because there were many parallel work-streams competing for these precious resources.

Modern cloud infrastructure changes the game. We can now provision entirely new environments in minutes if not seconds and consumption based billing makes that feasible also from a financial point of view. With this approach, developers each have their own isolated cloud environment. Setting this up usually means running a single command. Developers can then code and test against the actual setup. And more so, with infrastructure as code, they can test modifications immediately. These modifications are then checked in into version control along with the regular application code. This means these changes can be code reviewed and released along with the application. Think about full-stack development not just for front-end and back-end code, but also for infrastructure code. Teams can now own and take responsibility for the entire stack. Changes for new features, which often impact every tier, can be developed, tested and rolled out together. This removes friction and overhead between dev and ops.

Ok, enough of the benefits, let’s see how to make this happen. The rest of this article focusses mostly on automation of cloud resources and how to overcome specific challenges. This is an important part of in the journey towards Continuous Delivery, but there are certainly other parts that are just as important. For example, a modern development and release process requires a modern application. In part1, I’ve shared some good practices to build a back-end for the cloud. And as always, besides technology, there are culture and mindset aspects, which are often much more challenging to change.

Cloud infrastructure

A typical cloud native application does not only consist of application code deployed in containers or as functions. You usually have much more cloud infrastructure to configure, such as databases, blob storage, CDNs, etc. For this, it’s a good idea to split up these resources into different stacks, instead of adding everything to a single stack. By stack, I mean an infrastructure template that can be rolled out, such as a CloudFormation template or a Terraform template.

There are several reasons for using different stacks:

- Some resources might be slow to provision (looking at you, CloudFront, and at you APIM) or expensive (database instances)

- Some parts of the infrastructure may require additional change management / reviews

- You want those parts that change frequently (application code, functions, API changes, …) deployed as fast as possible and smaller templates help (also there may be some technical limitations regarding huge templates)

- You will have dependencies between different resources (more on this below)

Based on this, we typically see two different types of stacks:

- Shared base infrastructure stacks, that provision expensive resources that are going to be shared

- Functions along with their code, API mappings/routes and other cheap infrastructure deployed per developer, branch and/or pull request

This was very abstract, let’s talk about an example. Note that the decision about what services to share depend on the cloud provider, the service and your requirements. Services that don’t offer consumption based billing or are slow to provision are good candidates for shared resources. Otherwise you’ll spend a lot of money and/or time when provisioning a new environment (per developer, branch and/or pull request). In general, however, you want to avoid sharing wherever possible, because you don’t get the testing/isolation benefits.

For example we might decide to share a database and ElasticSearch cluster in our development environment. This will be our first stack. Rolling out changes to this stack can be a bit tricky, as they could potentially break your development environment. Shared stacks need to be carefully maintained (think about backwards compatibility, downtime, etc) and therefore deployment is usually done by a dedicated pipeline (not part of the app release pipeline).

Now let’s look at the parts that we want to deploy automatically in an isolated environment. That’s of course your function code, your API Gateway routes (or maybe even the entire gateway, if feasible), blobs, database schemas and tables, Elastic Search indexes, static assets of the front-end, etc. All this is part of our app release pipeline that gets automatically triggered for every branch and/or pull request. Note that in this example we have shared the database cluster, but the database schema/tables are not. This may require some code changes to your application to work with schema/table prefixes based on build pipeline parameters.

Continuous Integration

These days there are a lot of CI solutions on the market. Our choice has been and still is: Jenkins. That being said, the concepts described here should be translatable to other CI systems.

We usually have the following types of jobs:

- Shared infrastructure job that gets triggered manually and requires approval

- Out automated application pipeline (see below)

- A nightly job that cleans up resources of deleted branches and pull requests (Note to developers: Don’t forget to delete you remote branches after your feature is merged ;-))

Jenkins is a very flexible, battle proven automation server that has continuously improved over the years. With an endless number of plugins and multiple ways to configure pipelines, it can be a bit confusing to new users. Here’s what works very well for us:

Declarative pipelines and pipeline libraries

We’ve been using version control, code reviews and automated testing for application code for decades and the benefits are clear. And more recently we also treat infrastructure as code the same way. You definitely want to follow the same pattern for your CI pipelines and related configuration. Often enough I’ve seen teams configure complex jobs with complex parameters directly by using the Jenkins UI. Then changes get tested in a trial and error fashion by running the job. Granted, when Jenkins first launched some 15 (!) years ago, that was the only option to configure things. A lot has changed since then.

Pipeline libraries allow you to script your entire pipeline. Your build job then simply references a pipeline. The pipelines, stages and helper scripts can all live in a version controlled repository and your can then follow the same code review processes and standards as you already do for application code. With jenkins-pipeline-unit you can even run automated tests, catching many (but unfortunately not all) bugs before running the job in Jenkins.

I definitely recommend to build you pipeline mostly declaratively and with tedious things implemented in helpers and custom stages. This makes it easier to understand what the pipeline does.

Configuration Management

Similar to how your pipeline is described as code, you also want this for your configuration of the build job. Avoid having a lot of build parameters and instead load most of your configuration from a code repository or dedicated service. This way changes to configuration are also versioned and code reviewed.

We have most of our configuration in one or more configuration code repositories. This is another repository that does not contain application code. The JSON configuration files are located in directories following a specific hierarchy. The first step in all of our pipelines is to load the configuration based on a few parameters. Here’s what our Jenkinsfile of a multi-branch project looks like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

@Library('our-pipeline-library')

package jenkins.pipelines;

def myParams = [

'CLIENT': '...',

'APP': '...',

'REGION': '...',

'ENVIRONMENT': '...'

'STACK': '...',

]

withEnv(myParams.collect { key, value -> "${key}=${value}" }) {

pipelineServerless()

}

The parameters are not pipeline specific, they only describe how to load the configuration from the configuration repository. By using a hierarchy such as client -> app -> region -> environment -> stack, we can have some common configuration files at the top, and others overwriting specific values down at the individual stack.

Secret Management

Just like we do not hard-code passwords in application code or configuration files, the configuration repository does not contain passwords either. Instead, we make use of Secret Management services, such as Vault by HashiCorp, AWS Secrets Manager and Azure Key Vault. If a configuration value contains sensitive data, we add a reference to the record in the secret management solution instead. Our pipeline configuration helper then resolves the secrets accordingly. Here’s an example:

1

2

3

4

5

"appClientConfig": [

{ "key": "ClientName", "value" : "some client" },

{ "key": "ClientId", "value" : "ABCDEFG1234" },

{ "key": "ClientSecret", "value" : "//vault/path/to/secret/value" }

]

Pipeline Steps

For many applications, we deploy everything (infrastructure, front-end and back-end) together. As mentioned in the introduction, this is awesome, because features often require changes in all layers. This means there is a huge benefit to have a single pull request that contains all those changes.

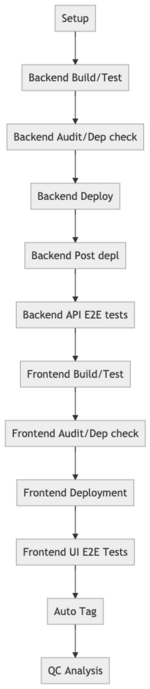

The figure on the left shows (a slightly simplified version of) the different stages of our Serverless pipeline. It gets triggered automatically when a branch or pull request is created. Some stages may be skipped, depending what branch is being built.

The setup step loads our configuration, as explained above. It may also do other initialization work such as loading secrets.

We start by building and unit testing our back-end API. We also check dependencies for vulnerabilities and license issues. If everything looks good the back-end API gets deployed. The deployment step deploys both, changes to infrastructure as well as application code. In the post deployment script, we may run some data initialization/migration tasks. The API E2E tests verify that the API deployment was successful and did not break the critical path.

The front-end invokes the back-end API and therefore it needs to know the base URL. This needs to be dynamically passed in from the previous build step, because each branch gets their own isolated environment (and thus its own URL). We perform similar steps to build, unit test and then deploy the front-end. A few E2E tests check that the site is not broken after the deployment.

If everything looks good, we tag the release (only for master builds) and run some more static analysis. Static analysis could arguably be done at an earlier stage and fail the build if it wasn’t successful. In practice the task can take a long time and we opted not to block us.

Wrapping up

Whew, this post became longer than I expected and I still feel like there’s a lot of info missing. I might update it in future. :) If you have feedback, questions or are missing some information, I would love to hear from you (via Twitter @restfulhead or see contact).